Between 1741 and 1841 the population grew from 1.9-2.2 million to 8.1-8.5 million but this was not matched by adequate expansion in much needed employment opportunities. [3] Against this background, a common theme that ran through the provision of public relief efforts during the Famine was the desire to avoid the allocation of ‘gratuitous’ or unearned assistance.

The perception that people required assistance was not due to a lack of willingness to provide for themselves. The tools to do this work though could be few to hand. Writing a ‘memorial’ to the Lord Lieutenant in 1837, Patrick M’Kye, a National School teacher in west Donegal, outlined the material resources available in the parish of Tullaghobegly. Amongst the agricultural tools available for a population of approximately 4,000 people, M’Kye listed a solitary plow, sixteen harrows, thirty-two rakes and twenty shovels.[4]

Some observers saw in the Irish poor an unwillingness to exert themselves to alleviate their poverty but the association of labourer and work was well known in other quarters. Travelling in Ireland in 1837, Gustave de Beaumont offered a sombre outlook that highlighted the limited circumstances available to many:

The Irish Catholic finds only one profession within his reach – and when he has not the capital necessary to become a farmer he digs the ground as a labourer…He who has not a spot of ground to cultivate dies of famine.[5]

If a livelihood could not be sustained at home, emigration offered for many an escape. A long-standing tradition was noted later in the twentieth century, that ‘Strong arms have been the Irish labourer’s passport to labouring jobs overseas’.[6] A less charitable view was expressed earlier by the civilian physician overseeing emigrants at Grosse Île, Quebec in 1846. He saw the Irish emigrants as being ‘ignorant of everything beyond the use of the spade’.[7]

Questions of who was ignorant aside, a different type of hunger developed over the course of the first half of the nineteenth century that demonstrated the utility of the spade. A hunger for land grew alongside population increase. More waste land was brought into use; cultivation of potatoes by the spade and the ‘lazy bed’ method being recognised for their ability to work this land and bring it to a state fit for grain crops.[8] One third of all land or 2.1 million acres was given over to potatoes in 1845 although this would fall dramatically and two years later was recorded at less than 0.3 million.[9]

Recognised as ‘the only earth-breaking hand implement of any importance in Ireland’, the spade, or loy, seen below, was a specialised tool suited particularly well to the smaller farms on poorer, boggy and rocky land.[10] This one-eared example came from county Longford. It was a type usually associated with the south and west of the country but the use of a spade in general, was country wide.

Loy (N.M.I. Collection – F:1937.43)

Whether as migratory labourers or spalpeens, such as in the image below, or labour given in exchange for a small plot of land or conacre, the spade was for many the necessary means to make a livelihood.

HOYFM.66.2009.52 ‘Sketch No. 55’ Sampson Towgood Roch[e], 1759 – 1847

Described by one observer as the currency of the peasantry, conacre necessitated an exchange of labour for a plot of land sufficient to grow a crop of potatoes. Set against a rent of £8 per acre, and a rate of labour exchange of 8d. (pence) per day, a labourer could be tied for 240 days service to his employer.[11] This costly exercise was made possible by land hunger and a plentiful labour supply.

In such cashless exchanges, and to avoid disputes, the bata scóir or tally-stick could be used as the means to record labour worked.[12] Associated later with punishing students for speaking Irish in school, the tally-stick has a longer history as a means to record business or legal transactions.[13] A stick split lengthways would be notched to keep track of time worked and one half kept by each of the respective parties.

Tally Stick (N.M.I. Collection – F:1909.70(A)

An overdue response to widely recognised poverty, the introduction of the 1838 Irish Poor Law was closely followed by an extensive construction programme of workhouses throughout Ireland.[14] These were built to accommodate the destitute poor. A core understanding for any able bodied person who gained admittance, was the requirement to work while a resident of the workhouse. The master of the workhouse was required to:

The range of labouring duties for a workhouse inmate could involve, amongst others, breaking stones, working on the workhouse land or other manual work in or about the workhouse.To provide for and enforce the employment of the able-bodied adult Paupers, during the whole of the hours of labour; to assist in training the youth in such employment as will best fit them for gaining their own living; to keep the partially disabled Paupers occupied to the extent of their ability; and to allow none who are capable of employment to be idle at any time.[15]

Hammer, ‘associated with Galway Workhouse’ (N.M.I. Collection - F:2000.245)

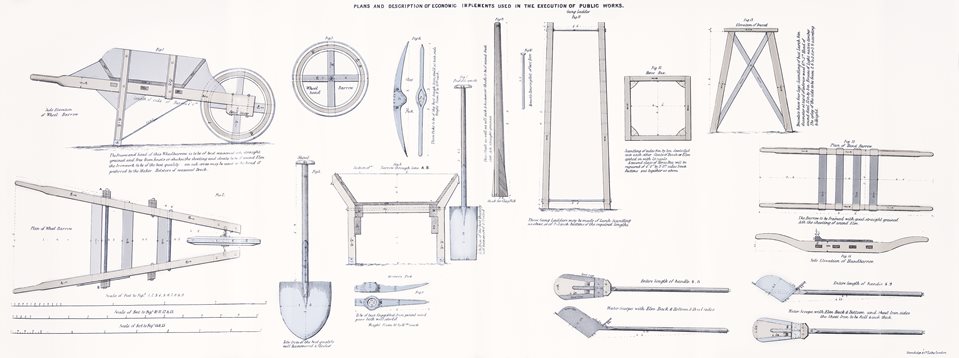

'Plans and Description of Economic Implements used in the execution of Public Works',

British Parliamentary Papers: Famine Ireland, Vol. 6, Irish University Press

Herein rested the fragile nature of a system with the potato as its linch-pin.[17] When the potato crop failed, a substantial portion of the population, existing already at near subsistence levels, had little in the way of reserves to tie them over. Their ability and means to provide for themselves was progressively weakened and the workhouse or public relief works struggled, and ultimately failed, to provide enough support to stave off hunger, disease and death.

Liam Doherty - Irish Folklife Division - National Museum of Ireland