She reached into the satchel. Through the acrid smoke and frozen mist the glint of the metal shrine, the goal of the raiders. They wanted to take the sacred book from within. No more would it be taken on circuits of the kingdom from Loch Cendin, it would no longer be their battle standard. Her family had protected the book for many years, her father begged her to save it as he lay dying on the edge of the island fortress. Examining the cumdach, she paused. There would be no getting at the sacred book inside without breaking it open ... but damaging the shrine front protected by its holy cross, the intertwined beasts and the shining golden bosses marking the wounds of Christ would surely bring damnation. She hurriedly worked to prize away the rivets, brackets and tubing which sealed the box, exposing the wood within. At the edge of the lake the raiding warriors pressed on over the ice … there was no time. Shouts from the shore, there would be no time to carry the shrine parts away ... levering open the sides, clutching the wooden boards protecting the holy words taken from inside, she would return for the other parts later. But how to conceal them? ... thinking quickly she wrapped them in cloth she had been keeping for reworking. With the packaged shrine now wrapped as multiple pieces thrust into her bag, she splashed along the low causeway … too late… the warriors approached and the bag slipped through the floating ice sherds into the reed beds and was sucked into the black lake silt.

There is of course no real way of knowing exactly how the Lough Kinale Book Shrine, the largest and earliest of Ireland’s book shrines or cumhdaigh ended up in the waters of Lough Kinale, Co. Longford close to a crannóg or island settlement. This ornate 9th-century shrine is the earliest of only eight early medieval book shrines from Ireland and the only one not to be modified in the later Middle Ages. Book shrines were elaborate containers for sacred books, particularly those associated with a particular saint. They embodied the power of the original book. The shrine was recovered by divers in 1986, and the National Museum of Ireland launched an extensive follow-up investigation. It has been under conservation since then and will be displayed in its entirety for the first time in Words on the Wave: Ireland and St. Gallen in Early Medieval Europe.

The shrine itself is remarkable, with a wooden box overlaid with tinned bronze plates, its cover taking a form similar to a cross-carpet page in a manuscript. This features a cast copper alloy cross inlaid with gilt intertwined beasts, and large circular bosses with amber studs mark the five wounds of Christ. A roundel in each quadrant of the cross contains openwork discs and amber studs. The edges are decorated with openwork strips with swirling motifs and birds. The sides are decorated with circular mounts containing cast beast heads and with internal circular openwork plates. A cast handle in the form of a beast would have been attached to each side and to leather straps for carrying. The top and sides were sealed by corner brackets and binding strips. Once the book was sealed within it would not have been possible to open it again without damaging the shrine. An examination of the geometry behind the shrine shows that it was meticulously planned from a single line using a dividers in the same way as illustrated manuscript pages were designed. The execution of the design in metal was more difficult and compromises meant that the result does not match its original mathematical plan. Unfinished beast heads and the rough nature of the decoration on the handles contrast with the beautiful openwork and show, like manuscripts, that several craftsmen with different levels of skill were involved. Just like the Irish manuscripts at St. Gallen, the combination of intertwined beasts, key patterns and Ultimate La Tène shows the influence of art styles from north-western Europe and the Mediterranean as well as older Irish art forms, which themselves had originated in Iron Age Central Europe.

How was it conserved?

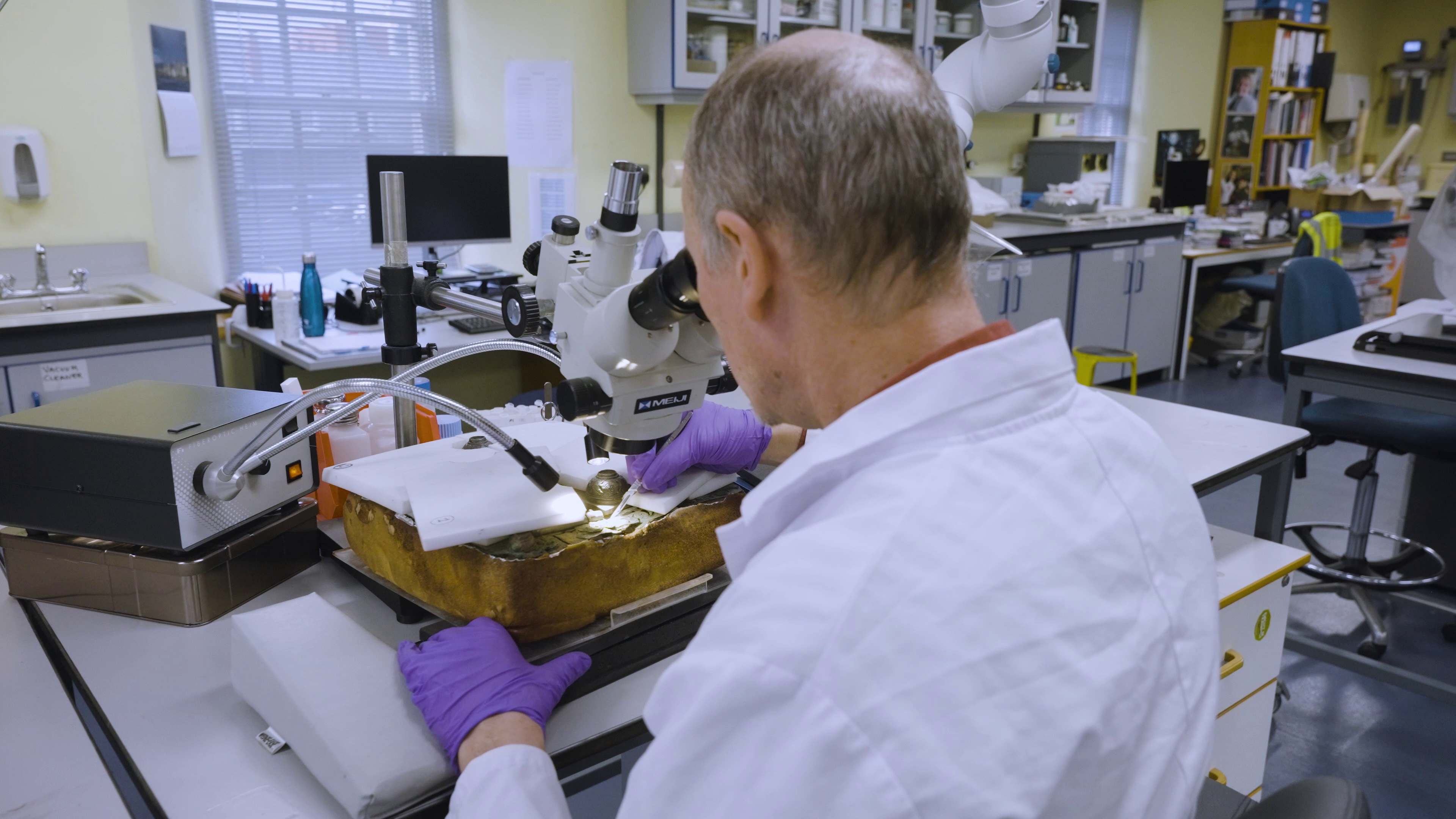

Conserving and cleaning the shrine was an extremely complex project undertaken at the National Museum of Ireland over many years. Treating a composite wooden and metal object was a very difficult undertaking as each requires very different conditions. The wood had to be treated first, followed by detailed analysis of the metal and meticulous mechanical cleaning of the corrosion on the metal fragments. X-Ray Fluorescence and X-Ray were used to examine each part to see how they were put together and what alloys were used to create the metal. Each of the components had to be taken apart and cleaned under a microscope to reveal the original detail.

.jpg)

The Lough Kinale Shrine being conserved in National Museum of Ireland Conservation Laboratories (Collateral films for National Museum of Ireland)

How did it end up lost in a lake in the Irish midlands?

Lough Kinale has numerous crannógs and has revealed a range of important finds including a simple chalice and paten of eighth/ninth-century date, which are being exhibited together for the first time, and a hoard of hack silver – bullion used as currency by the Vikings, with concentrations found in the lake powerbases of the overkingdom of Mide. The raiders may have been targeting a monastic site at the lake (Loch Cendin) where one Sechnasach, a bishop and anchorite (a recluse who prayed in solitude), died in 823 (Annals of Ulster).

Lough Kinale Crannóg (SMR: LF011-035-), Co. Longford (Discovery Programme)

Lough Kinale Crannóg (SMR: LF011-035-), Co. Longford (Discovery Programme)

How can a broken shrine be made whole?

Given that the object had been broken apart in the distant past, how could it be presented to the public in an understandable way? A team from the Discovery Programme, Ireland’s Centre for Archaeology and Innovation, partnered with the National Museum of Ireland to take many thousands of detailed photographs of all the shrine parts using a special turntable and lights in a darkened room, carried out over many visits. Photogrammetry software was used to create 3D digital models of each piece which could be manipulated. Exploring virtually how the fragments fitted together made conservators and curators think again about how parts of the shrine worked. This was particularly apparent when it came to the handles – how was the shrine held when a strap was attached? It was only when digital reconstruction was attempted that solutions to these issues were found. The remarkable result is both a spectacular and practical way of exploring this amazing object.

Staff from the Discovery Programme scanning a corner bracket of the Lough Kinale Shrine (National Museum of Ireland)

View of 3D interactive model which forms part of the Words on the Wave Exhibition (Discovery Programme)

View of 3D interactive model which forms part of the Words on the Wave Exhibition (Discovery Programme)

Would manuscripts like the Irish examples at St. Gallen ever have been in such a shrine?

While none of the Irish manuscripts at St. Gallen were held in a shrine, a related book called the Stowe or Lorrha Missal, which gave instructions for masses at different times of the year along with charms to cure illness, was enshrined from at least the eleventh century. There are similarities between it and two manuscript fragments from St. Gallen. One of these has a beautiful depiction of St Matthew and, on the reverse, charms or prayers in Irish for curing illnesses including a headache, urinary infections and an infection from a thorn (Cod. Sang. 1395, 418-9). The other is a cross-carpet page, with a liturgical ritual for consecrating baptismal water and salt on the other side (Cod. Sang. 1395, 422-3).

Manuscripts produced at St. Gallen were not placed within book shrines, but the most important of them did receive beautiful ornate covers. The Evangelium longum, a beautifully illuminated manuscript written at St Gallen, had an ornate jewelled cover with ivory plaques made for it by Tuotilo, a monk who had been trained by the schoolmaster Móengal in the ninth century (https://www.e-codices.ch/en/csg/0053/bindingA/0/). Covering books in this way was also a practice in Ireland – we can be reasonably sure that the Book of Kells was covered in gold from an annalistic reference in 1007, where it is said to have been stolen and stripped (Annals of Ulster).

The Lough Kinale Shrine remains a masterpiece of early Irish art.

This summer why not take this unique opportunity to see this treasure of Irish early medieval art and the manuscripts which would have been familiar to its makers.

Kelly, E.P. 1994 The Lough Kinale Book Shrine: the implications for the manuscripts, in F. O’Mahony (ed), The Book of Kells: Proceedings of a Conference at Trinity College Dublin, 6-9 September 1992, Aldershot, 280-289

Stevick, R. 2017 Morphogenesis of the Lough Kinale Book Shrine, front face, in C. Newman, M. Mannion and F. Gavin (eds), Islands in a global context, Four Courts Press, Dublin, 198-206.

Mullarkey, P. 2025 The Lough Kinale Book Shrine: conservation, decoration and technology in M. Seaver, D. Ó Riain and M. Sikora (eds), Words on the Wave: Ireland and St. Gallen in Early Medieval Europe, National Museum of Ireland, 68-73.