Love, Then and Now

One popular legend is that Valentine was a priest in Rome in the 3rd century AD who broke the ban on Christian marriage imposed by the Emperor Claudius, arranging marriages in secret. Valentine’s Day became a holiday in the 5th century, when Pope Gelasius I supposedly needed a convenient holiday to replace the pagan Roman festival of Lupercalia.

These various artefacts showcase and represent love and relationships through time. Whether you are at home or in the Museum, you can explore the stories below.

All artefacts are currently on display in the National Museum of Ireland, Collins Barracks.

Stop 1: Hair Sliotar and Caman, Curator’s Choice

The hurl in this case is called a camán, and beside it is a hurling ball or sliotar, of the type made from the 15th to 19th centuries, in Sneem, Co. Kerry. Sliotars made from matted cow hair with a plaited horsehair covering date from the 15th to the 19th centuries. Hurling balls were made as tokens of affection – love tokens – by young women and given to their favourite young hurlers for the Mayday celebrations and hurling contests.

Stop 2: Parnell Freedom Box, Out of Storage

This “Freedom Box”, was presented by the Nationalists of Drogheda to Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell in 1884. Parnell was leader of the Home Rule League and President of the Irish National Land League. Captain William O'Shea, Nationalist MP for County Clare, filed for divorce in 1889 from “Kitty” O’Shea, with Parnell named as co-respondent. This resulted in desertion by a majority of his Irish Parliamentary Party and losing position as leader. Adultery and divorce were deeply shocking at the time. Parnell and Kitty O’Shea married in 1891.

Stop 3: Figure of Venus and Cupid (bronze, Florence c.1750), Out of Storage

According to Roman mythology, the jealous goddess Venus commanded her son Cupid (god of love) to inspire Psyche (goddess of the soul) with love for the most despicable of men. Instead, Cupid placed Psyche in a remote palace where he could visit her secretly only in total darkness. One night Psyche lit a lamp and saw the god of love who then deserted her. Wandering in search of him, Psyche fell into the hands of Venus. Touched by her repentance, Cupid rescued her. At his instigation, Jupiter made her immortal and gave her in marriage to Cupid.

Stop 4: Standing or ‘Loving Cups’, 1674-79, Irish Silver

Typically the loving cup is a tall container with two handles, designed to be passed around at a wedding, to celebrate the happy couple’s union and symbolise the pledge they have made to one another. They were also for toasts at banquets and other ceremonial occasions.

Stop 5: Fans, The Way We Wore

The fan could be used to send specific messages to others. According to a guide to Victorian-era coded messages printed in Cassell’s Magazine in 1866, messages included:

“We are being watched” -- twirl fan in left hand

“I wish to speak to you” -- touch tip of fan with finger

“I love another” -- twirl fan in right hand

This ivory and hand-painted silk fan you can see here was made in France about 1780; it is decorated with gold and silver symbols of love. In a candle-lit room, the sparkle of its spangles would have drawn the eye to its user.

Stop 6: Trousseau Dress, Soldiers and Chiefs

This wedding dress was made for Livielia Stella Marguerita McIlwraith, the wife of Lt. Col. St. George Alexander Smith of Co. Meath. They got married in Australia in 1897. According to family tradition she did not wear it at their wedding in Melbourne but wore it in Ireland and referred to it as her 'wedding dress'. Many English soldiers married Irish women. Barracks men were usually securely employed so seen as desirable partners.

Stop 7: Sarah Curran Sewing Box and Robert Emmet’s Ring, Soldiers and Chiefs

Sarah Curran’s engagement to Robert Emmet was kept secret. Her father, lawyer John Philpot Curran, known for defending United Irishmen facing capital punishment for the 1798 rebellion, was against their relationship. In 1803, the United Irishmen led another rebellion against British rule in Ireland. Emmet escaped in the aftermath. It is believed he was on his way to meet Sarah before escaping to France. Sarah was disowned by her father and married a British Army Soldier. Following her death in 1808, her father refused to have her buried with her sister.

Stop 8: Kathleen Lynn Iodine Bottles, Soldiers and Chiefs

Dr Kathleen Lynn, Chief Medical Officer for the Irish Citizen’s Army during the 1916 Rising, met Madeleine ffrench-Mullen during involvement in revolutionary politics in Dublin. They then lived together for thirty years. Both were active in preparations for the Rising and imprisoned at different places. Their diaries reflect worry about not seeing one another, and excitement when reunited. Lynn was later moved to Mountjoy Prison and wrote: “I’d give £10,000 for Kilmainham and Madeleine”. There isn’t evidence of a sexual relationship, but diaries show they lived as intimate partners, often eating breakfast in bed together, and noting anniversaries.

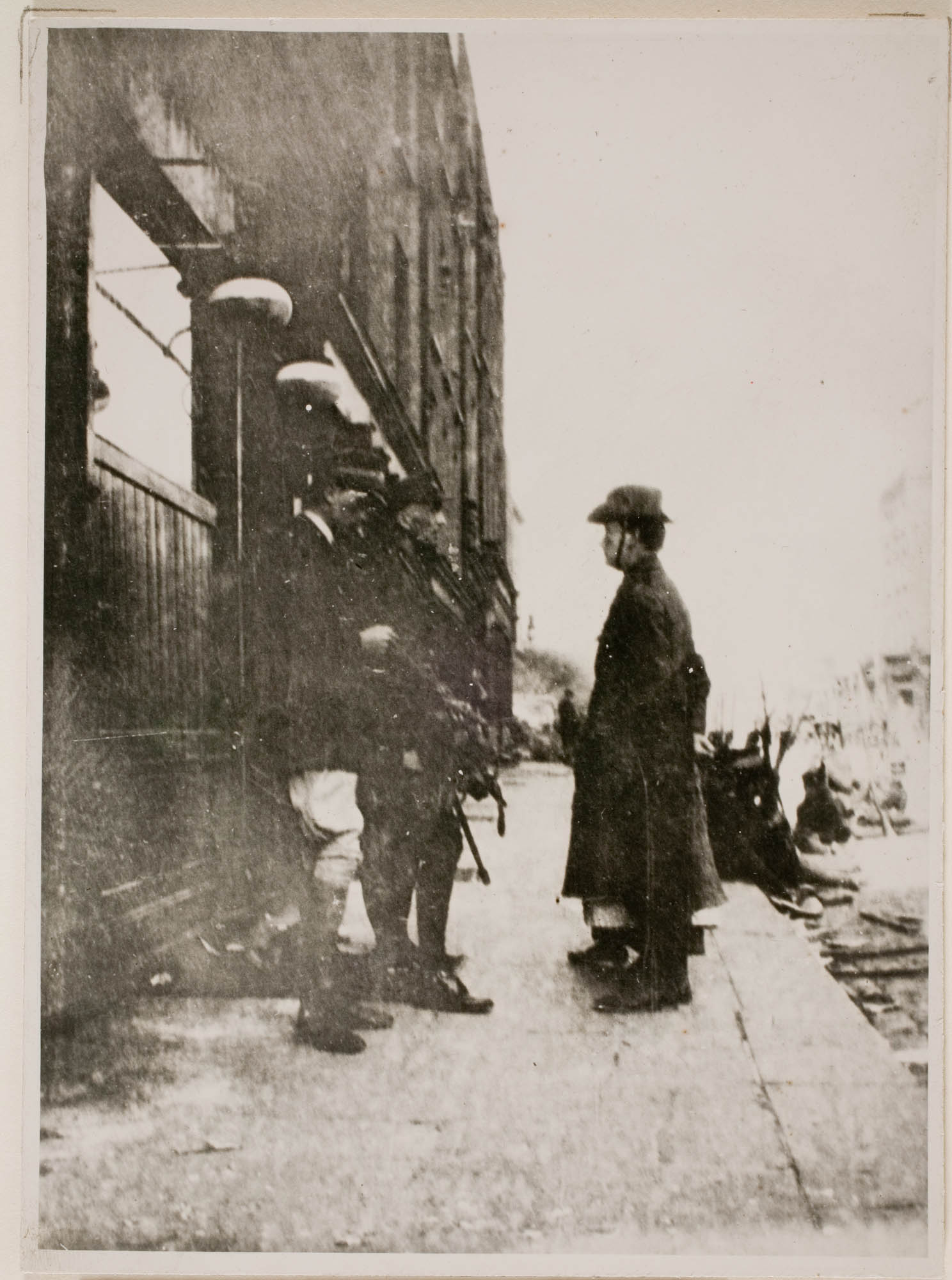

Stop 9: Surrender Photograph, Soldiers and Chiefs

This photograph shows Patrick Pearse with Elizabeth O’Farrell behind him: she escorted him when he offered the official surrender of the Easter 1916 rebels to General Lowe. Member of the Gaelic League and Inghinidhe na hÉireann, O’Farrell joined the ICA as a nurse with her partner Julia Grenan. They were stationed at the GPO providing medical assistance during the Rising. In O’Farrell’s death notice, Julia is given chief mourner position, often given to a widow/widower. Grenan was buried alongside O’Farrell under the inscription: “faithful comrade and lifelong friend,” coded language that might have been used to describe same-sex couples at the time.

See here for more virtual trails, learning resources and activity sheets.